Part 2 of 8

The Importance of Storytelling

Even with advanced technology that can synthesize and deliver quantitative data in actionable formats, further context and understanding of qualitative data and process feedback loops must be understood and assessed. As Nobel prize winners Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, were quoted in the book, “The Undoing Project,” by Michael Lewis, “No one ever made a decision because of a number. They need a story.”

Call it the “human experience side” of AI if you like. To ground us in reality and reasonable expectations, it helps to reflect on the early pioneers of behavioral economics, which is the study of psychology as it relates to the economic decision making processes of individuals and institutions.

What researchers in this area found was fascinating. Within studies on highly educated, scientifically disciplined professionals holding doctorates in medicine and statistics, Tversky and Kahneman found that most people walk around with mental heuristics (habits) including availability, representativeness, and anchoring. Their research indicated that all humans are prone to using recent availability or representativeness of personal experience to extrapolate probability, and our expectations can be anchored by the order in which we receive information — a humbling and troubling proposition. Many of us have seen this play out in corporate life, where diversity and meritocracy of ideas are often undercut by narrative shift, hindsight bias, and the poisoned wells of personality politics burying minority viewpoints calling for objective decisions.

Their groundbreaking findings were published in 1974 in a paper called “Judgment Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases”. Today, coupled with the birth and global domination of software, we increasingly look to technology for answers to protect us from misjudgment. However, there is a bit of humor here. As the proliferation of technology solutions further affirms, we need context and process to make the path realistic.

As the famous poem, “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” points out, a resource without calibration is nearly useless. “Water, water, everywhere, Nor any drop to drink…,” poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge wrote. Testing the experts, as Kahneman and Tversky found among their highly educated subjects decades ago, and being surrounded by numbers, is not relevant if it’s not digestible in our daily workflow.

To underline this point, Paul Slovic — a psychologist and a peer of Kahneman — decided to evaluate the effect of information on decision-making. He gathered a group of professional gamblers and tested them with horse races over four rounds. Slovic told them the test would consist of predicting 40 horse races in four consecutive rounds. In the first round, each gambler was given five pieces of information about each horse.

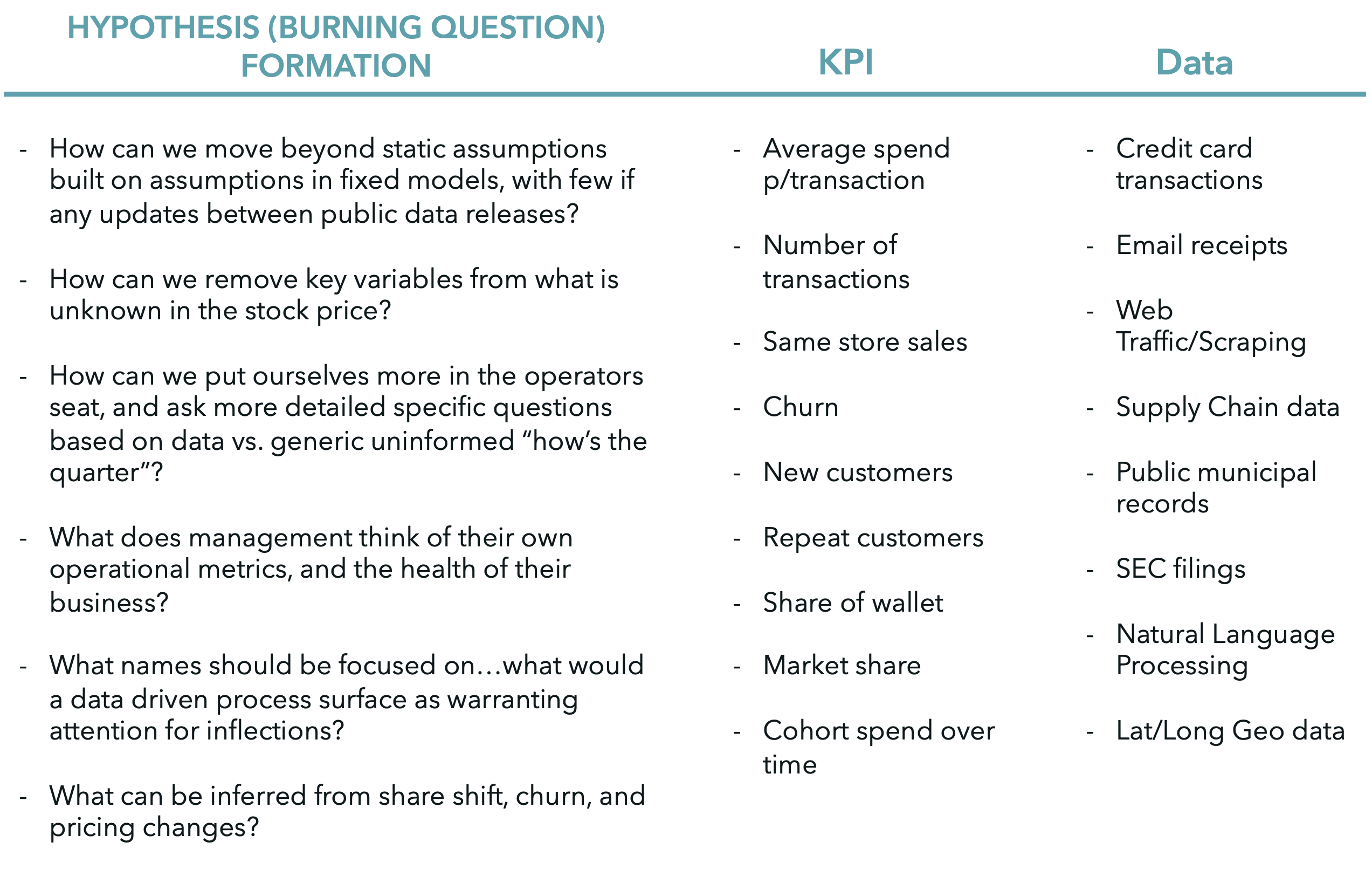

One might believe years of jockey experience was a key performance indicator (KPI); another might want horse top speed; and so on. Industry examples of these types of KPI calculations are shown in the chart above, “Business KPIs: A Universal Language”.

In addition to imageking winners, the experts were asked to indicate their level of confidence in their choice. In the first round with five pieces of information, they proved to be 17% accurate, substantially better than the 10% calculated chance prior to receiving their information. Their confidence was cited at 19%, relatively in line with the outcome. They were then given ten pieces of information in the second round and so on until they received forty pieces of information in the final round. Interestingly, while their predictive ability flatlined at the 17% accuracy level, their confidence continued to rise with the additional information to expect a 34% hit rate! story

This example shows significant ramifications in our human ability to use raw information often driven by a fear of missing out (FOMO) and untested assumptions. When blending qualitative and quantitative inputs, senior voices must be aware of the dominant heuristics and bias that may be present and must create pathways and processes for feedback loops to encourage input coming from junior employees, minority voices, and introverted personalities. Failure to include these additional inputs may be a travesty and lost opportunity for organizations who desire to grow and improve. Unless we have a disciplined consistent process with feedback loops, we risk simply cherry-picking inputs (whether qualitative or quantitative) to enhance our confirmation bias — leaving us both dangerously confident about our choices AND potentially blind to more optimal outcomes and solutions.

Read another article in this 8 part series:

- Part 1: Introduction

- Part 2: The Importance of Storytelling

- Part 3: Applying Process in Financial Workflow

- Part 4: Turning Questions into Predictions

- Part 5: ESG: Making Good Intentions Real Through Great Process

- Part 6: What is Driving the Stock?

- Part 7: Blending Inputs, Feedback Loops and Implementing Metrics the Matter

- Part 8: Bringing it Home and Upgrading your Roadmaps